|

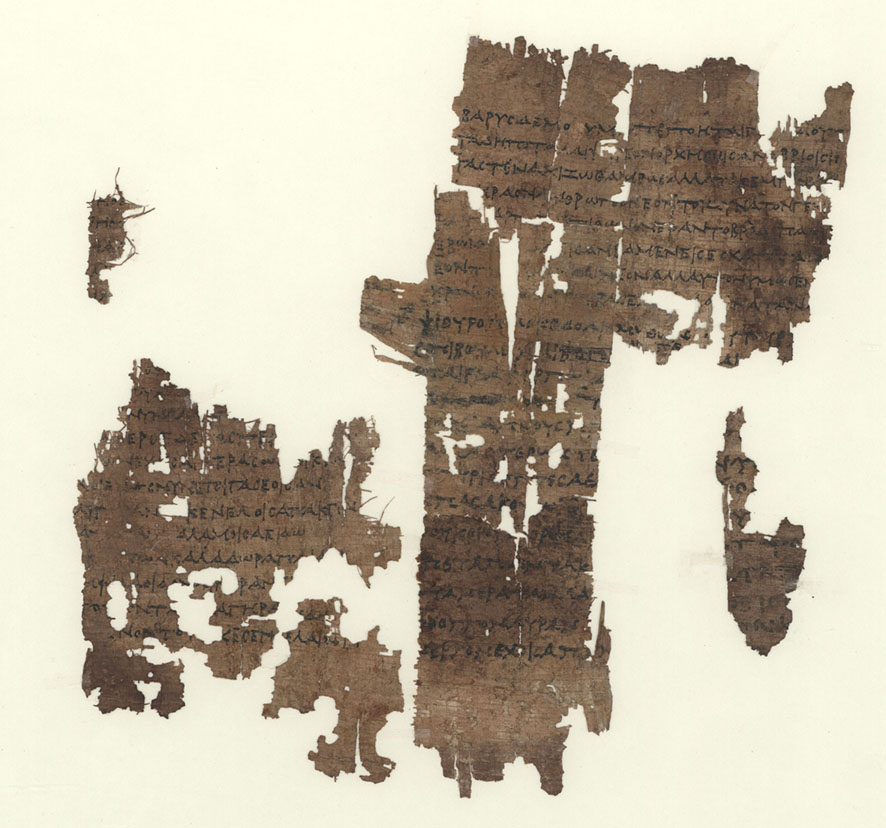

| P.Oxy. 1787 Sappho's Tithonos poem (fr. 58) |

Welcome to our Archival Expedition on The Textual Transmission of Female Greek Lyric Poets!

In three sessions we will gain an understanding of the textual transmission of Greek lyric poetry from antiquity to today and see examples of how papyri document Greek performative culture. We will learn to distinguish a high-quality papyrus bookroll from a cheap copy, dive into the history of the Duke papyrus collection, and explore the role of Hellenistic libraries and scholars in preserving, commenting on, and editing ancient literature.

At the end of this module, you will be able to navigate Greek papyrus bookrolls, modern papyrus editions, and scholarship on the material culture preserving female Greek lyric poets. The tabs on Digital Resources and Terminology introduce you to resources available in the field of Literary Papyrology and at Duke University.

For W Sept 16, 2020

Assignment

Papyrus as a witness of ancient reading culture & scribal practices.

Duke Prof. William Johnson is an expert in ancient reading culture and text production. As an introduction, watch his lecture From Bookroll to Codex (1 hour without Q&A) and answer the following questions in your notes:

- What characterizes a high-quality papyrus bookroll vs. a cheap copy?

- In which respects does an ancient text edition on papyrus differ from a modern one?

- Who were the readers of bookrolls in antiquity?

Optional: read or listen to

- A Biblical Mystery at Oxford (June 2020): The The Atlantic journalist Ariel Sabar investigates how the scholar in the leading university position of Papyrology at Oxford University gets entangled with the for-profit corporation Hobby Lobby and the black market of papyri. OR

- The Unbelievable Tale of Jesus's Wife (July/August 2016): The journalist Ariel Sabar uncovers the forgery of a sensational papyrus find. Either read his article in The Atlantic journal or listen to the podcasts of The Gospel of Jesus' Wife by Mark Goodacre, Frances Hill Fox Professor of Religious Studies at Duke University. Goodacre explains what The Gospel of Jesus' Wife is (NT Pod 87; 12 min), whether it is a forgery (NT Pod 88; 18.31min), how its forgery was proved (NT Pod 89; 18.44min), and how its forgery was confirmed (NT Pod 90; 18.56min).

Assignment

The history of the Duke Papyrus Collection & the provenance of papyri.

William H. Willis William H. Willis and John F. Oates joined the faculty of the Duke Department of Classical Studies in the 1960s and were leading papyrologists in the field. The two professors co-founded The Duke Databank of Documentary Papyri that gathers information about papyri worldwide and were instrumental in building the Duke papyri collection housed at the David. M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Read the 13-page article by William H. Willis (1985) on ➔ The Duke Papyri: A History of the Collection and answer the following questions in your notes:

- Why are papyri significant witnesses for ancient texts?

- Where do the Duke papyri come from? Critically review its sources and the ways in which it connects to other international papyrus collections.

For F Sept 18, 2020 & F Sept 25, 2020

Student Projects

Papyrological Research projects on Sappho & Corinna.

Investigate the textual transmission of one female Greek lyric poet in your research project and prepare a brief presentation. Briefly explain what makes your document interesting and show your findings on the digital image linked to your document. Tip: Comparing the papyrus transcription and image to your text edition helps you identify the places of interest.

Project: Sappho's hymn to Aphrodite (fr. 2)

Ostracon: PSI 13.1300

Comparing the papyrus transcription to your text edition, mark any scribal errors and deviations in the text. Be prepared to point them out on the archival image. Based on your findings, what level of literacy and proficiency do you think the scribe had?

Assignment

The Hellenistic scholars at work.

Read the ➔ chapters on The Library of the Museum and Hellenistic Scholarship and Other Hellenistic Work (14 pages in total) and answer the following questions in your notes:

- Does the Hellenistic scholarship on ancient texts differ from today's scholarship in Classical Studies? Why/why not?

- How did the Hellenistic scholars leave their imprint on our modern text editions?

If you have any questions about an assignment, contact sinja.kuppers@alumni.duke.edu.